Gopher Tortoise: Building a thriving community

Down along the Florida panhandle, a gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) finds its way through a community of burrows as morning sunlight cascades across the forest floor. One of the tortoise’s many burrow mates, an Eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos), emerges and slithers indifferently beyond the burrow’s edge to find a warm spot to sunbathe for the day. Typically, instances such as this one are considered unusual. Remarkably however, the interactions between the gopher tortoise and other wildlife are actually commensal. These creatures benefit from gopher tortoises, but do not affect them in any way. In fact, without the gopher tortoise, the ecosystem in which the tortoise lives, along with the wildlife in it, would change drastically.

An eastern hognose snake (Heterodon platirhinos) and a gopher tortoise (Gopherus Polyphemus) sunbathing outside a tortoise burrow.

Scenes of co-existence are common for the gopher tortoise as over 350 different species use their burrows for housing, nesting sites, and even temporary refuge from predators or naturally occurring forest fires. Many of these burrow inhabitants are incapable of creating their own shelter and rely on the engineering skills of the gopher tortoise to survive, earning the tortoise the title of keystone species. Unfortunately for the gopher tortoise and its burrow mates, populations were heavily affected in recent decades by disease, invasive species competition, and most devastatingly, habitat loss from rapid urban development. As a result, gopher tortoises experienced an 80 percent decline in the last one-hundred years, prompting Florida to protect the gopher tortoise as a state-designated threatened species through the state’s Endangered and Threatened Species Rule. The gopher tortoise is also federally listed in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana and is under review in the rest of their distribution.

The gopher tortoise still faces serious threats from Florida developers who obtained incidental take permits acknowledging that tortoises exist on a given plot of land tagged for construction and allowing developers to build on top of identified burrows—as of 2006, contractors entombed 13,000 tortoises. Given the rate of development on existing gopher tortoise habitat, researchers estimated 25,000 tortoises could still become entombed in the near future, labeling them “zombie tortoises” as they are considered walking dead.

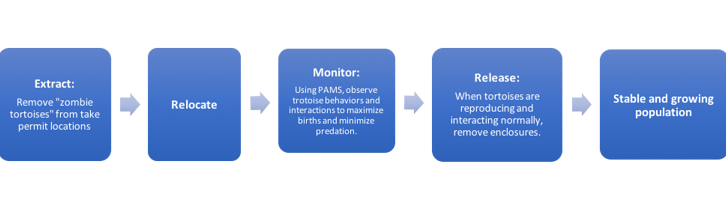

A snapshot of gopher tortoise relocation

A means for translocation

In response to this unfortunate situation, the Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute (NRI) researchers, including Drs. Wade Ryberg, Danielle Walkup, Toby Hibbitts and Brandon Bowers, are working in partnership with many private landowners and stakeholders to relocate these “zombie tortoises” to new, development-free habitats.

Relocated tortoises are placed into large enclosures to encourage acclimation to their new location while also safely detaining tortoises, who instinctively attempt to travel back to their original homes. This method facilitates the establishment of a new community within the enclosed area, prompting reproduction and, subsequently, population growth. Though the process appears simple, one of the many variables of this effort includes the unknown timeline between translocation and reproduction. Typically, wildlife will refrain from reproducing in unfamiliar locations until they become comfortable; a process that could take anywhere from months to years in the case of the gopher tortoise.

Monitoring for success

Once relocated, Passive Automated Monitoring Systems (PAMS) are set up around the enclosure to photograph activity every 60 seconds, allowing researchers to monitor and analyze tortoise movements as well as the surrounding dynamics within the community, helping determine gopher tortoise condition post-relocation. This ideal type of monitoring allows researchers to collect high-quality data without interfering with gopher tortoise behavior.

Before PAMS, theorized challenges like predation were difficult to prove. By implementing PAMS, several instances of predation have already been documented—including an adult gopher tortoise being carried off by a coyote (below). As a major feat for gopher tortoise research, not only does this type of monitoring support theories, it defines the next course of action for eliminating factors inhibiting population growth.

Adult translocated gopher tortoise being carried off by a coyote.

Captured using NRI’s Passive Automated Monitoring Systems (PAMS).

Forward Movement

As of November 2018, the combined conservation efforts of NRI and numerous private landowners and stakeholders saved more than 1,000 at-risk gopher tortoises from an uncertain future, while also encouraging population growth in new, long-term environments. This collaboration is only the beginning for other wildlife affected by gopher tortoise populations and can serve as a model for many at-risk species affected by human co-existence issues. Thanks to additional granted funding, NRI researchers aim to continue their work to provide this species a life well lived.

--

Literature cited:

- Keystone Species. Retrieved here.

- Gopher tortoise: Gopherus Polyphemus retrieved here.

- Staff members of the Jacksonville Ecological Field Office. (2009). Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; a 90-day Finding on a Petition to List the Eastern Population of Gopher Tortoise (Gopherus Polyhemus) as Threatened. Federal Register, 74.

- Pierce, Bryan. (2018, May 11). Acoustic Monitoring: Redefining innovation on the prairie. Retrieved here.

- Rules Relating to Endangered or Threatened Species. (2010, November 8). Retrieved here.

- Gopher Tortoise, Gopherus Polyhemus. U.S. Fish and Wild Life Service. Web.

--

Edited by Dr. Wade Ryberg, Dr. Toby Hibbitts, Brittany Wegner, Alison Lund and Dr. Jim Cathey