Private Land Stewardship: The Importance of Knowing Your Animals

It is important as a landowner to know which wildlife species frequent your property and how to alter your management practices in order to benefit those animals. Gaining a better understanding of common wildlife as well as species you may never encounter will not only make you a more informed wildlife enthusiast, it can provide you with a well-rounded approach to private land stewardship. Most landowners commonly observe generalist species like white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginanus) or raccoons (Procyon lotor) on their property, but among the ecoregions of Texas there is vast diversity in habitat that many species call home. This article will discuss several distinctive species that a Texas landowner might encounter and provide insight into their individual management needs.

Ring-tailed Cat

The ring-tailed cat (Bassariscus astutus) is actually not a cat at all; it is a member of the raccoon family that can be found throughout most of the state in areas with oaks (Quercus spp.) or pinyon pine (Pinus edulis). These nocturnal omnivores are excellent climbers that live around rocky areas like talus slopes, canyon walls, and vertical surfaces that other species can’t scale. Ring-tailed cats, or “ringtails,” consume a wide variety of foods ranging from the fruits of junipers (Juniperus spp.) and hackberries (Celtis spp.) to prey species including cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus) and rock squirrels (Spermophilus variegatus; Toweill et al. 1977). Their nocturnal lifestyle and solitary nature help them stay so well-hidden that some Texans may not even be aware they exist. However, if your property is full of potential food sources and rocky hideouts, you may be able to catch a glimpse of a ringtail at night using trail cameras. These animals are often also inadvertently observed while using spotlights to conduct wildlife surveys for game species.

A ring-tailed cat sitting in a tree (left) and a map of their distribution (right). Photo from the U.S. National Park Service and map from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

Ringtails are charismatic creatures that display behaviors not found in other Texas species. One particularly unique behavior is their ability to climb between vertical walls with four feet on one wall and their back pressed against the other, known as “chimney stemming” (Trapp 1972). They can also rotate their hind feet 180 degrees, allowing for rapid descents down vertical surfaces (Trapp 1972). While more research is needed on the conservation status of ring-tailed cats, they are considered to be relatively abundant across their known range.

Golden-cheeked Warbler

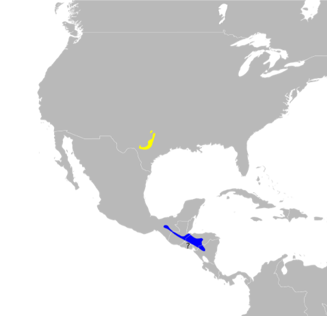

A clear contrast to the wide distribution of the ring-tailed cat is the relatively small nesting habitat of the golden-cheeked warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia). This migratory songbird nests exclusively in the Texas hill country each year from March to July after wintering in Mexico and Central America. They build their nests using strips of native Ashe juniper (Juniperus ashei), or “cedar” bark that is plentiful across their nesting range and prefer to live in thick, older growth juniper forests. The golden-cheeked warbler has been listed as an endangered species since 1990, and NRI research efforts have helped to better understand their decline by studying factors such as habitat loss and fragmentation in the Edwards Plateau due to urban development (Robinson et al. 2018) and the impact of anthropomorphic sounds on golden-cheeked warblers (Lackey et al. 2011). These studies found that habitat fragmentation plays an important role in the viability of the golden-cheeked warbler and the best habitat for them includes oak-juniper woodlands greater than 26 hectares (64.2 acres) in size with a canopy cover of at least 70% (Robinson et al. 2018). Additionally, they concluded urban construction and road sounds do not appear to significantly impact warbler territory choice or reproductive success (Lackey et al. 2011). The rarity of these songbirds makes them a unique and valued annual visitor to the state of Texas. Widespread and sustained conservation efforts to preserve their natural woodland habitat remains the best management practice to manage for golden-cheeked warbler habitat.

A golden-cheeked warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia) and a distribution map of their wintering range in Central America (blue) and nesting range within Texas (yellow). Photos from Jason Crotty and Birds of North America Online.

Barton Springs Salamander

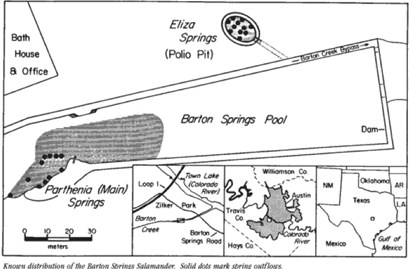

The golden-cheeked warbler is far from being the only endangered species with an extremely limited Texas distribution. The Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum) can only be found in one place in the world: the outflows of Barton Springs in the Edwards Plateau. They are entirely aquatic throughout their lives and can range from dark gray to purple in color. They must live in a continuous flow of clean, clear water so they can capture oxygen from the water using their red and frilly external gills. The Barton Springs salamander is vulnerable to human threats such as urban development, runoff, risks of chemical and sewage spills, and reduced groundwater availability. Restoring aquatic plants to the pool and minimizing harmful practices when maintaining the pool are examples of ways in which wildlife managers ensure the purity and safety of Barton Springs so that it remains a suitable place for these rare salamanders to thrive. Water conservation efforts within the Edwards Aquifer recharge or contribution zones, among other watershed management techniques, remain integral to the long term success of the Barton Springs Salamander.

A Barton Springs salamander (Eurycea sosorum) and a map of their distribution (black dots indicate spring outflows where they are found). Photos from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Bluegill

Unlike the rare Barton Springs salamander, most fishermen in Texas have encountered the ubiquitous bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) and can testify to their abundance in Texas waterways. They have spines along the front of their dorsal/anal fins and can be distinguished from other sunfish species by the dark spot at the soft base of the dorsal fin. Bluegills are extremely popular fish for stocking ponds and lakes and will bite at almost any bait put into the water. They also serve as an important forage species for many larger gamefish including largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris; Stone 2008). Their range extends throughout Texas and North America. Bluegills have an extended spawning season that peaks in early summer and lasts until water temperatures drop below 70°F, so they can quickly become overabundant in ponds and smaller bodies of water. This can result in a stunted population in a stocked pond without adequate predation or fishing pressures (Wisconsin DNR 2008). Many Texans have fond memories of fishing for bluegills and other sunfish as young children, and they will thankfully remain a part of Texas tradition for generations to come.

Bluegills (Lepomis macrochirus) are members of the sunfish family that occur throughout North America. Photo by Jon Nelson.

Conclusion

Texas is home to over 600 species of birds, 243 taxa of native land mammals, and around 225 species of reptiles and amphibians. While encounters with species such as ring-tailed cats, Barton Springs salamanders, and golden-cheeked warblers are often rare, abundant species like bluegill can be difficult to avoid at times. Nevertheless, each native species holds some intrinsic value and offers ecosystem services that are vital components to our natural world. A general knowledge of animals and an understanding of the roles each play in the ecosystem is an amazing tool in our land stewardship toolbox, and this knowledge can contribute to more conscientious land management decisions that benefit the productivity of the whole ecosystem for many generations.

To learn some more about interesting Texas species, visit TPWD’s fact sheets here.

--

Literature Cited:

- Lackey, M.A., M.L. Morrison, N. Fisher, S.L. Farrell, B.A. Collier, and R.N. Wilkins. 2011. Effects of road construction noise on the endangered golden-cheeked warbler. Wildlife Society Bulletin 35(1):15-19.

- Lewellen, G.T. 2003. Bassariscus astutus (ringtail). West Texas A&M University Mammalogy Lab, fall 2003. Canyon, TX. http://www.wtamu.edu/~rmatlack/Mammalogy/Species_accounts_2003/Bassariscus_astutus_account.htm

- Robinson, D.H., H.A. Mathewson, M.L. Morrison, and R.N. Wilkins. 2018. Habitat effects on golden-cheeked warbler productivity in an urban landscape. Wildlife Society Bulletin 42(1): 48-56.

- Stone, N. 2008. Forage fish – introduction and species. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center. SRAC Publication No. 140. http://www2.ca.uky.edu/wkrec/foragespecies.pdf

- Toweill, D.E. and J.G. Teer. 1977. Food habits of ringtails in the Edwards Plateau region of Texas. Journal of Mammalogy 58: 660-663.

- Trapp, G.R. 1972. Some anatomical and behavioral adaptation of ringtails, Bassariscus astutus. Journal of Mammalogy 53: 549-557.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Bureau of Fisheries Management. Bluegill. PUBL-FM-711 08. http://dnr.wi.gov/topic/fishing/documents/species/bluegill.pdf