Wild Pig Wars: Controversy Over Hunting, Trapping

Wild Pig Wars: Controversy Over Hunting, Trapping in Missouri

By Chris Bennett

Farm Journal

Technology and Issues Editor

--

Click here to jump to the battle in Texas.

Under gray skies on a fall morning, Rick Clubb wears an expression of disbelief as he walks across 10 acres of strafe-bombed pasture and stares down at ground turned upside down overnight. Wild pigs have unleashed hell. Again. The field is flipped and cratered, green gone brown in multiple stretches, testament to the wrecking ball capacity of a phenomenally opportunistic survivor. Head in hands, Clubb rubs his temples as the proverbial dollars drain from his pockets, keenly aware of the stark reality on his southeast Missouri farm: The wild pigs always return. “I call it the hog apocalypse,” he says. “They’re multiplying so fast and nobody in my state wants to damn well admit it.”

Wildlife officials contend current wild pig controls are extremely effective, but a chorus of landowners claims the number of wild pigs in Missouri is climbing. A chasm of disagreement separates the two sides, centered on the efficacy of the Missouri Department of Conservation’s (MDC) no-hunting policy. MDC officials insist the trapping-only method is highly potent and conducive to eventual elimination of wild pigs in the Show-Me State, while some landowners believe the no-hunting approach is a recipe for a population increase. With forced reliance on anecdotal evidence and no official population estimates, the controversy highlights an uncomfortable truth: There is little room for error when dealing with the most reproductively prolific large mammal in North America.

A Trail of Numbers

In June 2016, MDC banned the hunting of wild pigs on roughly 1,000 conservation areas and initiated a no-hunting policy, directing the public to follow a “Report, Don’t Shoot” strategy. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers followed suit and instituted the MDC no-hunting policy on its properties, while the USDA Forest Service essentially also mirrored MDC action, but currently allows “incidental take” of wild pigs.

Mark McLain, feral hog elimination team leader with MDC, says trapping, by itself, is the top method to eliminate wild pig populations. Hunting, he explains, is an impediment to trapping efficacy. “Targeting the entire group at once with a trap is the best way to remove the group, then strategically move on to the next group, and with time, eliminate the population. When feral hogs are hunted, a hunter may be able to shoot one or two in a group, but then the rest of the hogs in the group scatter, often onto neighboring property.”

As a certified wildlife biologist with MDC, Alan Leary backs McLain’s stance. “Trapping is the No. 1 way to effectively eliminate feral hogs. We’re currently seeing successes in some parts of the state. This is a concerted effort beyond MDC, but we’re going to get there and eliminate these hogs from the state of Missouri.”

“We banned the taking of feral hogs on all MDC-controlled land—owned, managed or leased,” Leary continues. “If people are allowed to pursue feral hogs, that boosts the incentive for illegal releases. The majority of people obey the law, but we know people are doing this and that’s why populations expand.”

USDA-APHIS maintains 29 full-time trappers in Missouri, and the no-hunting policy is successful, claim Leary and McLain. MDC has divided wild pig populations into smaller working areas, and placed trappers in each area to strategically remove wild pigs and then monitor the area for illegal releases, McLain describes: “The areas with smaller hog populations have seen a great reduction of known feral hogs; other areas are going to take more time to see the same reduction.”

By calendar year, wild pigs removed through trapping in Missouri are on the rise, and the statistics are touted by MDC as indicative of an increasingly successful program: 5,358 in 2016; 6,567 in 2017; and 9,365 in 2018. Yet, significantly, MDC has no approximation of wild pig numbers. “The Missouri Department of Conservation does not have an estimate of the population of feral hogs in Missouri,” McLain says.

“Right now, we don’t know the feral hog population in Missouri and have no way to estimate the number,” Leary echoes. “We know trapping is working and diminishing populations because we see fewer signs of damage from feral hogs.”

“I see us in five or 10 years showing eliminated populations of feral hogs across the state,” he adds.

Cody Norris, public affairs officer with Mark Twain National Forest, also says no wild pig population evaluation is currently possible. “There is no accurate estimate of how many feral swine are in our forest due to uncontrolled variables related (to) human influences such as introduction and moving of individual pigs, fragmented and remote landscapes.”

However, a Mark Twain National Forest publication (Forest Reflections2017, page 10) released in June 2018, contradicts the absence of a wild pig approximation, and projects numbers at “an estimated 20,000 – 30,000 feral hogs in the State of Missouri.” Whether viewed from the low or high end, if the Forest Reflections tally is correct, MDC wild pig trapping numbers are far below conventional control rates.

What do MDC’s trapping numbers mean? Are 9,365 wild pigs trapped in 2018 a result of an effective policy, or a sign of a rapidly increasing wild pig population? Wild pigs reproduce at an outrageously high rate, with sows typically delivering two litters (each litter averages six piglets) in 15 months. Females are reproductively capable at five to six months, fueling the multiplier effect. Generally, wild pig biologists often place the “control” bar at roughly 66% to 75%. In theory, taken at 66%, if a given area has a wild pig population of 100,000, then 66,000 pigs must be culled each year—simply to maintain the population of 100,000.

Extrapolating, if 9,365 wild pigs trapped in 2018 meets the precise 66% threshold necessary for population stasis, Missouri has a wild pig population of 14,189. Or, if 9,365 wild pigs trapped represents a far higher rate than 66%, Missouri’s wild pig population is markedly lower than 14,189. Conversely, if Missouri’s trapping numbers point to a rate much lower than the 66% bar, the stage is set for a surge in wild pig numbers. (Taken at a high of 30,000 in the Forest Reflections estimate, MDC’s 2018 trapping number of 9,365 wild pigs indicates a substantially low control rate of 31%.) Regardless of outcome, the chilling math highlights the complexities of wild pig control.

Bollinger County landowner and hunter Allen Morris calls MDC’s numbers “fantasy” and “denial of an exploding crisis.”

“MDC says trapping-only is working and is going to fix the problem in just a few years? Look around. There is a feral hog explosion going on in our state and I don’t believe that MDC is unaware of what the wild pig estimate is. Of course they don’t know the exact total, but you can bet they have a ballpark figure or a range. MDC, a professional conservation org, literally has no clue what the hog population is? If they literally don’t know, then what the hell do the trapping numbers mean?”

“They’re telling the public that 9,000-plus hogs trapped is eliminating the population. No way. I hope I’m just flat wrong about all of this, but I believe hog numbers are going nuts. If MDC thinks their trapping numbers are taking care of the problem, then we don’t have any hope of stopping the hogs.”

One Size Fits All?

Outside the small town of Greenville, in Wayne County, Rick Clubb maintains a small herd of 30 cows spread across 200 acres of hills and hollows. His property, roughly a mile from Wappapello Lake, rubs against land controlled by the Corps and Forest Service. Wild pigs have traditionally maintained a limited presence around Clubb, but in 2005, he began noting a rise in numbers, and the past five years, he says, have given rise to a notably sharp spike. “Nobody is allowed to hunt the hogs on the government land, so they stay in there and flood out at night, destroying fields like you can’t believe.”

Damage to Clubb’s pasture spurred him toward a $13,000 no till drill, plus recurring costs of seed and fertilizer. “A year or two to get a really good stand? I’m just a small farmer and I can’t keep spending money, but I’ve lost so much grass to the rooting. I try to keep a constant watch but there are so many pigs and it’s always a matter of time before they show back up to root.”

“What am I supposed to do? Hunting with dogs is the only way that’s worked to keep them out of here. Yes, I’ve tried trapping and there’s one thing they don’t understand at the wildlife department: You can’t trap your way outta this problem because one size don’t fit all.”

Feet on the Ground

Morris owns 80 acres of closed canopy forest connected to 157 acres of adjacent MDC ground beside the Castor River, and has a front-row seat to what he labels a “giant hole” in MDC’s no-hunting policy. Due to baiting regulations, trapping and deer season don’t mix. Translation: USDA trappers can’t access particular blocks of land during deer season from September to January (as well as April turkey season). The implications of trapping absence for an approximate four-month span raise substantial concerns, Morris claims, particularly when the animal in question can put feet on the ground faster than any large mammal in North America. “We’re dealing with a hog that can drop piglets in any month of the year. What animal gives birth in the open in January and expects offspring to survive? Only a wild hog. So MDC won’t trap for months in some areas while deer season is going on, and won’t allow anyone to shoot hogs there either? That is a formula for increased hog numbers and I call it what it is—a guaranteed hog refuge.”

Despite Morris’ alarm, Leary believes the eradication plan is working and says such concerns lack merit: “We (MDC) have trapping restrictions due to baiting rules during deer and turkey season. But trappers still can work and stay busy on private landowner spots. They have to adjust their trapping in fall, but they still trap year round somewhere.”

“Trapping restrictions do not create safe havens or refuges at all,” Leary adds. “As we continue to drop the populations, we may have to makes changes to our regulations. At this point, there are no significant problems and this is working.”

McLain contends trapping is the only viable wild pig solution for Missouri. Hunting, he says, is ineffectual and a detriment to trapping, “…we know hunting feral hogs spreads the problem, while trapping a whole sounder at a time is effective in removing the problem from a landscape.”

Morris, however, says state officials are incorrect: “MDC tells the public they’re going to completely eradicate and eliminate wild hogs—the greatest survival creature in this country that is basically a plague in the states around the Bootheel. Then they claim zero knowledge of the number of hogs in the state, but don’t hesitate to tell the media and the public all the latest trapping numbers? Something is not adding up and nobody wants to acknowledge this craziness.”

Advocating a “wild hog control” policy, Morris offers three preventive measures:

1. Allow individual deer hunters to shoot wild pigs. “The woods are already crawling with deer hunters and there are gunshots everywhere, so we’re already making a ton of pressure. Killing at least a few more hogs won’t make the pressure any worse.”

2. Allow baiting on private land. “Dump the outdated regulations and give us a permit system. Again, it sure as hell won’t make things worse.”

3. Allow hog-doggers to remove hogs with a permit system. “We’ve got terrain that can’t be trapped and the only way to get a hog is with a dog. Dog teams could be a valuable resource, especially in certain geographies. I’ve heard people run down hog-doggers and put all the blame on the entire community for illegal hog releases. There’s blame alright, except it doesn’t belong on hog-doggers—it belongs everywhere. Forget blame; I just want to control these hogs, but it may be too late.”

Bacon and Eggs

“You ever seen a bomb go off in a pasture?” asks Rob Elder. “That’s what it looks like from just a night of wild hogs.”

Elder, who lives in Wayne County and serves as communications director for the Missouri Hunting and Working Dog Alliance (MHWDA), says trapping and hunting could go hand-in-hand for wild pig control. Pared down, Elder says trapping should be coordinated alongside tracking with trained hunting dogs. “Trapping is not consistently effective in catching mature hogs. Yes, you can catch part of the sounder, but you create trap-shy adults. That’s where well-trained dog teams could come in and hit hard against adult hogs.”

“Does the public even know that trappers can’t go in certain areas for months at a time? That’s called a hog safe-haven. I’ve heard all the arguments: If they let in dog teams to hunt then the pressure will push the hogs to another place. Seriously? There’s 300,000 or more hunters blasting rifles at deer in the exact same woods and MDC is worried about us moving the hogs?”

“I feel like the public is being misled. I believe we are in a hog epidemic and there is no other animal like this to compare with. We’ve only got 29 full-time USDA trappers for the state, and MDC is telling everyone that wild hogs will be eradicated in just a few years. Listen, any landowner or farmer in southeast Missouri can tell you we’ve got places with terrain so difficult that you can’t even get a trap in there. Thank the Lord for the landowners on private land still killing hogs by any means possible. I can’t imagine how bad the hog problems in this state would be if all private landowners quit killing hogs and instead called the MDC to ‘Report, Don’t Shoot.’ Are you kidding?”

Elder insists he is overwhelmed by calls from private landowners consistently asking for help with wild pig removal. He and fellow MHWDA members reportedly killed 1,871 wild pigs with dog teams in 2018. “We try to provide a service to our communities, but we’re portrayed as the bad guys. This is as simple as bacon and eggs: Eradication is not happening and the bureaucracy is a logjam. MDC does a lot of great things, but this hog approach is not one of’em.”

“Trap the young and the dumb hogs, and send coordinated dog teams after the rest, because you either get those trap-wise adults or you’re pissing in the wind.”

Total Eradication

Hunting of any sort has exacerbated the wild pig problem in Missouri, says Eric Lemons, natural resources specialist at Wappapello Project Office with the Corps. In the Wappapello area, increased wild pig presence surfaced in 2002, and the Corps responded by asking the public for hunting help. The result, according to Lemons, was a major population jump. “People called from all over the country wanting to hunt them and it actually built a hunting culture that was negative to what we were actually trying to accomplish. For 10 years plus, we let people come in and hunt at will or trap by permit, but the only thing happened was an increase in hogs.”

The Corps is part of the Strategic Elimination Plan, developed by the Feral Hog Partnership with federal, state and non-government orgs. Lemons is adamant: The best avenue for wild control is a trapping-only pursuit. “Hunting did not work and does not work,” he says.

Even permitting deer hunters to kill wild pigs is detrimental and a “double-edged sword,” Lemons explains. “It goes against everything we’re saying as far as ‘Report, Don’t Shoot.’ For instance, if 20 hogs walk by you might be able to kill one or two, but we could catch the entire 20 hogs in a trap. When hunting is allowed, it incorporates a management tool that does not lead to complete eradication. We know that baiting and trapping is the most effective means.”

In addition, hog-doggers upend the overall wild pig management strategy, Lemons details: “Many times we will be getting hogs on bait, and see a dog on the game camera and a week’s worth of work is gone because the sounder moves.”

Backing McLain and Leary, Lemons says the current no-trapping policy is extremely effectual (500 wild pigs trapped at Wappapello in 2018) toward a goal of “total eradication” of wild pigs. “The statewide plan is in place and highly effective. The biggest piece of the puzzle is landowner cooperation. For this to be successful everybody in the state has to get on board with eradication and get away from the idea of having hogs to hunt.”

“This Is A War”

Lemon’s position is contrasted by James Gracey, who spent eight years as assistant operations manager at Wappapello. After a 40-year career with the Corps, retired (September 2018) district supervisor and professional forester Gracey doesn’t mince words in regard to wild pigs. “The ultimate goal is to kill hogs and this is a war. In war, you use your entire arsenal. Send in the army, navy, air force and marines.”

Gracey advocates trapping combined with strategic hunting. “The reality that nobody seems to be willing to acknowledge is that there are only so many state employees and traps. Look at the terrain in many places where vehicles can’t even get access to trap. However, the man with a dog gets in and he’s a valuable tool to shoot hogs. Bottom line, there is room for everyone to play a role in this and we all should be working together. Dog hunters are good people and they’re not transporting hogs and they constantly help people kill hogs in areas where boot leather is required, despite the rap they frequently take.”

Deer and turkey season leave major wild pig gaps that “defy logic,” Gracey details. “September to January is deer and April is turkey, and meanwhile there is no trapping in those hunting areas while the hogs breed? Let the deer hunters help and kill at least some of these hogs. There are thousands and thousands of deer hunters chasing whitetail all over the woods and you can be sure the hogs are going to move anyhow. The goal is supposed be to kill hogs, so at the very least incidental takes should not be outlawed. Everyone needs to be involved to stop the most prolific breeding animal in the woods.”

“If we’re all reasonable, the public will truly get behind this hog effort and maybe it’s not too late. I’ve seen the USDA trapping numbers, but I don’t know what they mean if nobody has an estimate of the hog population. Of course nobody expects precision, but it’s almost impossible for me to believe nobody in the entire state has a clue of our wild hog population. Not even a high or low, or even a range? One thing for certain: I wouldn’t boast about trapping numbers without knowing the overall hog population, because the public is going to catch on and it makes everything look suspect.”

Bayou Beasts

The Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) estimates its wild pig population at 700,000. Significantly, LDWF also estimates hunters harvested 130,600 wild pigs in 2016-2017. Currently, in wildlife management areas, Louisiana allows the shooting of wild pigs during any open hunting season. Retired LDWF Captain Bobby Buatt believes a multi-pronged approach is necessary to control wild pig populations over the long-term. “All methods to control hogs have successes and downfalls, and that’s why I’m a firm believer in utilizing everything whether trapping, shooting, or hunting with dogs.”

Buatt, a 30-year veteran, insists on the efficacy of firearms and points to deer hunters in given wildlife management areas as an example: “On the opening of deer season, you might have 400 hunters on a particular refuge. Regardless of what your regulations are, the presence of these guys pressures all the game, including hogs, to get up and move around. That’s 400 direct opportunities to kill hogs that shouldn’t be missed. You then multiply that across the entire state and across the entire deer season and you’re talking major league hog kills.”

LDWF places the control rate of wild pigs in order to maintain a static population at 75%. “I’m all for trapping and getting as many hogs as possible through all means. But the reality is you’re trapping on hundreds of thousands of acres with how many trappers and how many traps? They can only cover a small area. The hunters are everywhere and they’ve got eyes open—let’em go. I don’t ever want Louisiana hunters or dog teams to be taken out of any equation because they are a resource to be utilized.”

Texas Trouble

While Louisiana has a stout wild pig population, and Missouri presumably has a relatively small population, Texas wears a painful crown at the top of the porcine heap in the U.S., as home to roughly 3 million wild pigs. The Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute (NRI) places the control rate to maintain wild pig populations at 66%. In stripped-down parlance: Texas needs to remove approximately 2 million wild pigs per year to keep 3 million wild pigs on the landscape.

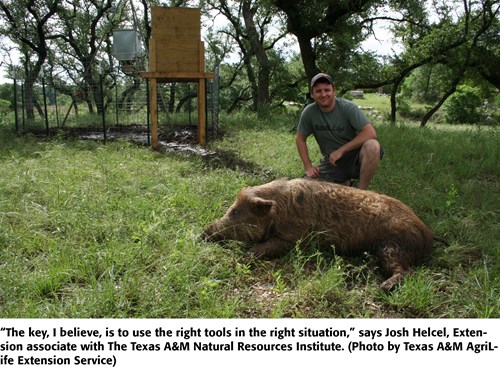

As an Extension associate with NRI, Josh Helcel specializes in educating Texans on wild pig biology, impacts and control: “Research indicates that annual wild pig removal rates in Texas are roughly half of what they would need to be to maintain current population levels. Wild pigs are an intelligent and adaptable species, and best management practices include utilizing a combined approach of all available tools to reduce their numbers and damages.”

Helcel advocates trapping as “generally the most effective tool readily available to the average landowner,” and says trapping success is often increased when used exclusively in a given area. As for the efficacy of shooting from deer stands or ‘Report, Don’t Shoot’ approaches, Helcel says the slippery task of wild pig control makes each circumstance unique. What works in one situation may be entirely ineffective in another, he explains. “People on all sides may not like to hear it, but the answer is usually, ‘It depends.’ It’s tough to take a blanket approach to control because factors including resource availability, hunting/trapping pressure, geography and others can vary greatly even within a single county. Shooting, for example, can be effective in reducing wild pig damages if the situation is a fit for that tool. The key, I believe, is to use the right tools in the right situation.”

What about dog teams? According to Helcel, “When and how trained dog teams are used can be paramount to their overall effectiveness as a control technique. Dogs are capable of removing wild pigs that weren't able to be removed following the enactment of other strategies. Research shows that trained dogs are most effectively used on residual populations as a final tool of sequenced control efforts."

Tennessee’s Good and Bad

MDC’s insistence on the eventual elimination of wild pig presence is noteworthy, particularly considering the proliferation of wild pigs in neighboring states, and the porcine capacity for reproduction. Missouri is saddled with a perpetual geographical wild pig dilemma: The Show-Me State can’t change its neighbors, particularly states with a significantly high wild pig presence: Arkansas, Oklahoma and Tennessee. The wild pig saga in Tennessee holds lessons for Missouri—both good and bad.

On state land, which is only 1% of all land in Tennessee, TWRA doesn’t trap wild pigs during bear, deer or turkey season. “It’s not ideal and we know it because the hog populations can rebound, but we are forced to manage our public Wildlife Management Areas for much more than just wild hogs,” says Joy Sweaney, a wildlife biologist with Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA). “Overall, we focus on maintaining the integrity of the big game season in order to not compromise big game hunter success. However, private landowners can bait and control wild hogs all year.”

Tennessee has long dealt with established wild pig presence, but the numbers generally were confined to particular regions, Sweaney explains. In 1999, when the wild pig season was opened statewide, the balance changed as wild pig populations popped up across the state, attributable most likely to illegal transport—car wheels.

In 2011, Tennessee made wild pig trapping a priority on TWRA-managed lands. “This was the best method,” Sweaney describes. “We went after sounders with great success and made big dents in reproductive capability.”

In addition, TWRA established a landowner exemption program, and gave landowners relative freedom in controlling wild pigs. “We gave the landowners power. Basically, we offered an exemption and a green light to use methods beyond what was traditionally legal. Bait, spotlight, or whatever, as long they reported the number of hogs killed in order to renew the exemption. Each landowner could also give 10 people designee permission to control hogs.”

And the results? TWRA mostly eliminated wild pigs in many of the new areas where wild pigs had surfaced, according to Sweaney. “We had a lot of success in the new areas and the majority of our state presently doesn’t have hogs. However, in the areas that have traditionally had hogs, I don’t think anyone would claim we’re reducing the population, but we’ve managed to hold the tide.”

As of the last TWRA estimate in 2012, Tennessee’s wild pig population stood at 135,000.

“Not Here”

I don’t have any complicated answers for what is happening. I’m a simple, common sense guy.”

Steve Branch maintains a small cattle herd in Ellsinore, and the Carter County producer frequently finds wild pig-damaged patches on his 70 acres of pasture surrounded on three sides by government land—holes that often stretch 5’ across and 6”-8” deep.

Wild pigs emerged onto Branch’s land in 2012, arriving with force. “One way or another, half my acreage is affected. Hit one of those holes with a tractor and see how it feels, or look at one of my reseeding bills and see how that hurts.”

Trapping once produced major results on Branch’s ground—30 wild pigs at a time. “The ones I didn’t catch got wise. I’ve brought in guys hunting with dogs and they’ve been a tremendous help. I absolutely believe in trapping, but no way is it a one-way solution. There’s parts of this land where it’s impossible to trap. If the officials believe trapping-only is a sure-fire means to tackle hogs, then maybe they’re talking about some other state. Not here.”

“All I ever hear is eradication. I don’t know what species the state officials are talking about, but the one on my land is crazy for survival, smart like no other animal, and spreads like wildfire. I’ve had officials tell me they’re doing great and trapping their way out of this problem. No sir. I’m not even sure how to answer that kind of talk. I’m just a small farmer and I want everyone involved to act reasonably. I don’t think I’m the only guy that feels like that.”

A Farmer Torn

Forty-five miles east of Branch, just outside Puxico in Stoddard County, Chuck Stewart is a farmer torn by the wild pig controversy. “I’ve picked no sides here and I’m a big supporter of MDC. The best thing for everyone is plain talk and openness, because I’m not sure anyone knows what is really going down.”

“Right now, it’s really easy to take shots at the conservation people, but I personally know so many of those guys are really good people and just want to do the right thing. The problem is there isn’t necessarily any way for anybody on any side to do the ‘right thing’ when you’re talking about an animal like no other.”

Stewart lives in the hills and farms in the flats, growing 3,300 acres of corn, cotton, rice and soybeans, a stone’s throw from the Mingo National Wildlife Refuge. Wild pig trouble is a relatively recent problem for Stewart, with sounders sometimes tearing into his corn fields or damaging rice levees. “Get close to the refuge and hogs are a serious issue for landowners, but just a few miles away, those guys may not have any hogs—yet. Hogs are still spotty, and that’s what makes it so tough on MDC trying to come up with a number. Still, it’s tough for me to swallow that they don’t have any general idea of how many hogs they’re dealing with.”

Two USDA-affiliated trappers operate in the Puxico vicinity, and the pair does an “excellent” job, Stewart describes. Three hundred acres of his farm are subject to wild pig depredation, and trapping is “highly effective” on his operation, he attests. “Done right, trapping works tremendously well. It’s the single best weapon out there.”

Pared down, Stewart finds himself straddling both sides of the wild pig fence as a proponent of trapping and hunting. “I sure hope MDC is getting it right, because if things aren’t exactly like they say, then we ain’t seen nothing yet. I’m a big believer in MDC and they help landowners in so many ways, but they’ve never explained how in the hell they’re going to trap in these hollers and achieve this eradication they talk about. I want them to be right, but in my opinion they’re going to be fighting these hogs long-term, as in forever, and it seems like they can’t admit that for political reasons or something.”

No matter what policy MDC pursuits, Stewart believes the endgame is a no-win situation. “Everybody involved in this, no matter where they stand, has some right-and-wrong on their heads. Meanwhile, I’m afraid the damn hogs are going to survive, but I sure hope I’m totally wrong. Another thing, I want MDC to get full backing and funding to fight these hogs, but if a man finds a hog in the woods, he oughta be able to shoot it. Even if you say no to hog-doggers, at least let somebody in a deer stand kill a hog if it walks by.”

Better and Bad

Wild pig depredation hammers the U.S. economy each year, costing as much as $2.5 billion in damage, according to the National Feral Swine Management Program (NFSDMP). Nationwide population estimates vary, but Jack Mayer, highly reputed manager of the Environmental Sciences and Biotechnology Group at the Savannah River National Laboratory in Aiken, S.C., places the approximate U.S. wild pig tally at 6.3 million, with an overall estimate ranging between 4.4 million to 11.3 million.

When considering the potential long-term damage to Missouri landowners and wildlife from wild pig presence, how will the ongoing battle play out?

Leary maintains a sanguine outlook and places full faith in the current policies. “We believe if we continue to implement our Strategic Plan, feral hogs will be eliminated from Missouri,” he notes. “We believe we can eliminate feral hogs in the Bootheel, even though the terrain has challenges.”

“The message I want to get out is ‘Report and don’t shoot.’ Even on private property, if you see feral hogs, just contact MDC or USDA, rather than shoot them. We’ll come out and trap and work with the landowner to eliminate all the feral hogs,” Leary concludes.

Opposing the MDC stance, Morris sees increasing problems on the horizon. “In just five years or so, if MDC is right, then hogs will be no problem, but I’m afraid MDC is walking into a gunfight with a knife. I don’t believe we’re getting close to a hog crisis in Missouri—we’re already in crisis. We’re over the hump and I think anyone who genuinely believes wild hogs are going to be eradicated in my state is kidding themselves.”

Looking across bare dirt yet to be planted, Stewart knows the wild pigs again will descend on his corn and rice in 2019. Pulled between competing emotions of hope and doubt, the Stoddard County farmer voices strong backing for MDC, but wrestles with the overall wild pig approach. “The fault here, at least in my area, started with outlaws releasing hogs to hunt, so I don’t blame MDC for nothing, but the things I hear now don’t always make sense. Why not just have a plan that is about long-term control and that hopes to hell to keep them in check? I’m not a big talker and I try to stay balanced. When I hear promises for elimination or eradication, I feel like it’s an overreach that helps nobody.”

“I want to be fair and call it like I see it because these hogs are destructive at billions of dollars in damage every year across the country,” Stewart concludes. “That’s the kinda high stakes we’re dealing with in Missouri and things could get better, but they could also get bad—really bad.”

--