Coping with the Cold

Bobwhite rooster and hen in winter. Photo by Missouri Department of Conservation.

Winter is one of the most biologically and environmentally stressful times for quail. Colder weather requires individuals to expend large amounts energy just to maintain a steady body temperature, requiring them to burn 25% more energy in order to survive10. This need, coupled with the increased energy requirements associated with reproduction in the following spring months, makes this a period when energy demands are extremely high11. Scaled quail will begin to select mates as early as late-February, and Gambel’s quail will begin to breed in mid-to late February following a cool, wet winter3.

Inconveniently, this spike in energy needs corresponds with the time of the year when food resources are least abundant, increasing the risk of starvation and creating a major challenge for wild quail. A study in west Texas found that winter availability of broomweed seeds affected both bobwhite and scaled quail diets and the morphology of their digestive tract6. Broomweed seeds had the highest energy content per gram of available winter food sources and quail would consume significantly less green vegetation if broomweed seeds were available6. If seeds were not available, both species would increase their intake of relatively low energy green vegetation to meet their nutritional demands and elongate their small intestine and ceca to be able to extract more nutrients6. The study found that scaled quail seemed better equipped than bobwhites to adjust their digestive organs to extract more energy from their food and accumulate more lipid reserves when seed availability was limited.

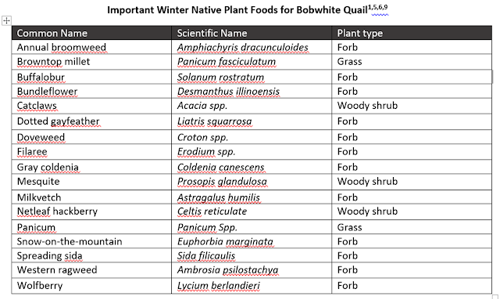

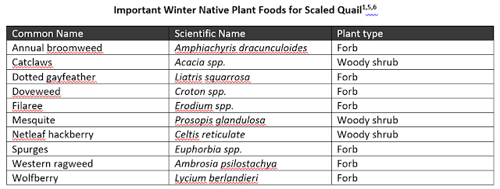

All species of Texas quail depend on a variety of food sources throughout the winter months, including grass and forb seeds, green vegetation, insects, and mast3. A study of quail food habits in southwest Texas revealed bobwhite winter diets consisted of 72% green vegetation, 20% seeds/fruits and 6% animal matter, whereas scaled quail diets consisted of 52% green vegetation, 38% seeds/fruits and 2% animal matter in the fall-winter1. Beetles, grasshoppers, stinkbugs, termites, leafhoppers, ants, and butterfly and moth larvae have been recorded by multiple studies as being important cold-weather staples in quail diets1,2,13.

Sorghum and wheat from food plots, scattered waste and unharvested fields, can provide an invaluable supplemental food source to help maintain coveys through the harsh winter months9. Robel and Kemp 1997 found that quail had a greater chance of survival near food plots since they had increased food availability and in turn were able to accumulate more fat reserves. Food plots need to be effectively managed since consumption of food resources by other species can render them useless to quail in the late winter, especially in the months of January-March7.

Quail require a variety of plant food sources to get them through the tough winter months. From the top left clockwise: Snow-on-the-mountain, Broomweed, Catclaw acacia and Western ragweed.

Freezing is another major cause of quail winter mortality10. Robel and Kemp (1997) found that low temperatures in January and periods of snow cover significantly increased winter mortality of bobwhites, both by chilling the birds themselves and preventing them from finding food. Despite being small, primarily ground-dwelling birds, Texas quail are hardy and are able to cope remarkably well with winter conditions provided they have adequate cover. Essential thermal and loafing cover varies for each species, but can include bunchgrasses, shrubs, trees and bases of rocks in the case of the Montezuma quail3. Evergreens like various junipers (Juniperus spp.) provide excellent thermal cover against north winds. Quail that covey-up for the fall and winter may have an extra advantage, as the covey roosts in a tight circle (heads out, tail in) to keep warm and has more eyes looking out for predators and food.

A major cause of winter mortality in quail is freezing. Photo by Missouri Department of Conservation.

As if freezing temperatures and lack of food were not enough to worry about, there is also an increased threat of predation during the winter months. Scarcity of resources means that quail have to cover more ground and, in the process, expose themselves to predators. Raptors (e.g., Cooper’s hawks (Accipiter cooperii), Northern harriers (Circus cyaneus)) are typically more abundant during winter months, and can exact a toll on quails. A study of overwinter survival of quail in Kansas found avian and mammalian predators accounted for 55% of mortality of their radiomarked bobwhites7. Researchers in Tennessee reported that changes in landscape structure, specifically increased abundance of closed canopy forest edge within covey home ranges, increased overwinter bobwhite mortality14. This may have been due to 2 reasons. First, bobwhite activity along the forest edge may have rendered the birds vulnerable as they moved between open habitats with herbaceous ground cover into forests with little or no herbaceous cover14. Second, the abundance of forest edge may have boosted overall predator abundance and/or efficiency, giving predators the advantage in these otherwise suitable habitat spaces14.

Cooper's hawks are a common avian predator of quail.

Photo by Johann Schumacher/Vireo

Life for a quail is never easy, but it gets even tougher in winter. The combination of decreased food resources and increased energy requirements can cause a large amount of metabolic stress for these small birds. Sparse cover and increased foraging time also leave quail exposed to both avian and mammalian predators. By making the best of a limited food supply, relying on their covey and using the cover available, quail can beat the odds and survive to see the spring.

Literature Cited

- Campbell-Kissock, L., Blankenship, L.H. and Stewart, J.W. 1985. Plant and animal foods of bobwhite and scaled quail southwest Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist. 30: 543-553.

- Davis, C.A., Barkley, R.C., and Haussamen, W.C. 1975. Scaled quail foods in southeastern New Mexico. Journal of Wildlife Management. 39:496-502.

- Frank, M., Ruppert, K., and Cathey, J. 2017. Habitat requirements of Texas quail. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service EWF-096.

- Lam, L. 2016. The Coldest Temperatures Ever Recorded in All 50 States. The Weather Channel. https://weather.com/news/climate/news/coldest-temperature-recorded-50-states.

- Lehman, V.W., and Ward, H. 1941. Some plants valuable to quail in southwestern Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management. 5:131-135.

- Leif, A.P. and Smith, L.M. 1993. Winter diet quality, gut morphology and condition of northern bobwhite and scaled quail in west Texas. Journal of Field Ornithology. 64: 527-538.

- Madison, L.A., Robel, R.J., and Jones, D.P. 2002. Hunting mortality and overwinter survival of northern bobwhites relative to food plots in Kansas. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 30: 1120-1127.

- National Weather Service. n.d. Climatology of Snowfall in the Panhandles. https://www.weather.gov/ama/snow_climo#1.

- Parmalee, P. W. 1955. Notes on the winter foods of Bobwhite in north-central Texas. Texas Journal of Science. 7:189-195.

- Quail Forever. n.d. Effects of weather combines with habitat to impact quail numbers. https://quailforever.org/Habitat/Why-Habitat/Quail-Facts/Effects-of-Weather.aspx.

- Robel, R.J. 1963. Fall and winter food habits of 150 bobwhite quail in Riley County, Kansas. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 66: 778-789.

- Robel, R.J. and Kemp, K.E. 1997. Winter mortality of northern bobwhites: effects of food plots and weather. The Southwestern Naturalist. 42: 59-67.

- Rollins, D. 1980. Comparative ecology of bobwhite and scaled quail in mesquite grassland habitats. M.S. Thesis, Oklahoma State Univ., Stillwater

- Seckinger, E.M., Burger, Jr., L.W., Whittington, R., Houston, A. and Carlisle, R. 2008. Effects of landscape composition on winter survival of northern bobwhites. Journal of Wildlife Management. 72: 959-969.

A covey of scaled quail, photo courtesy of Deb Whitecotton

A covey of scaled quail, photo courtesy of Deb Whitecotton