The Western Chicken Turtle

Page 1: Shells and Scutes

Turtles have a number of adaptations for protection. In addition to their shells, many turtles have hinged vertebrae that allow them to draw most of their head and neck straight back into their shells.

A turtle skeleton.

A turtle’s shell is essentially a ribcage that has been adapted for better protection. In this skeleton of a softshell turtle, it is easy to relate the shell of a turtle to the ribcage of its ancestors:

Skeleton of a softshell turtle.

In most turtles, the bone grows to cover both the top and bottom of the turtle. The rounded top half of the turtle’s shell is called the carapace. The flatter, bottom half is called the plastron. This is a Western Chicken Turtle:

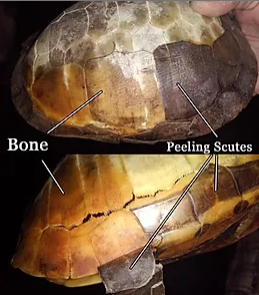

The shell of most turtles is composed mainly of solid bone, but is covered in keratinous laminae called scutes (similar to scales). These scutes flake off and are replaced regularly, just like shedding skin in other reptiles. In these photos you can see a chicken turtle that has been eaten by a predator. The remaining shell was left in the elements, so many of the scutes have flaked off, revealing the bone beneath:

A predated turtle with exposed bone and peeling shell scutes

Page 2: Identification

The Western Chicken Turtle (Deirocelys reticularia) is a mid-sized turtle with a smooth, hard shell. They can grow up to 10 inches in length and are usually tan to olive green.

The Latin name reticularia means “net-like” and refers to the net-like pattern of lighter colored rings on its shell. The turtle species that most commonly shares habitat with the chicken turtle is the red-eared slider, so knowing the difference between them is important.

Western Chicken Turtle

Red-Eared Slider

The easiest way to identify a chicken turtle is by looking at the front legs. It is the only species within its range that has one solid yellow bar on each front leg. The hind legs can be a good secondary identifier, as this species has vertical yellow stripes across its rump. The red-eared slider has multiple, thinner stripes on each forelimb and a random pattern of yellow ovals or circles on its hind limbs.

A chicken turtle with the easily identifiable single thick bar across its front legs.

A red-eared slider with multiple pin stripes across its front legs.

Chicken turtles have vertical stripes across their rumps.

Red-eared sliders have circles or oval-shaped blotches on their hind legs.

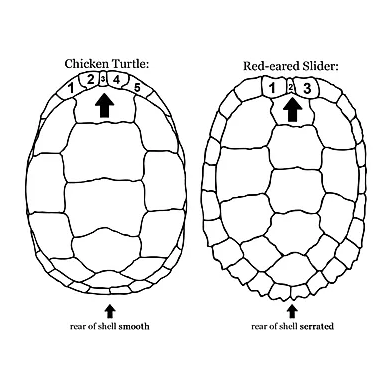

If you only have a shell to identify, you can identify a chicken turtle by looking at the first dorsal scute (scale). The first dorsal scute is shown at left with an arrow. Chicken Turtles are the only species within its range in which the first dorsal scute touches five of the scutes on the edge of its shell (with the exception of the yellow mud turtle, which will not have the striped rump). The rear of the chicken turtle’s shell is smooth, while most of the similar species within its range have serrations on the rear of their shells.

A diagram comparison between the shells of chicken turtles and red-eared sliders.

Page 3: Habitat

In Texas, chicken turtles usually live in ephemeral wetlands from February to July, then migrate to upland estivation sites and bury underground for the remainder of summer, fall, and winter.

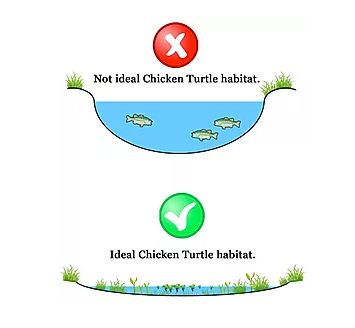

Chicken turtles prefer shallow, still, gently sloping wetlands that dry up from time to time. Dense aquatic vegetation is an important component of their habitat. Though they will occasionally use roadside ditches when traveling from wetland to wetland, they are not usually found in the moving waters of streams, creeks, or rivers.

Vegetation is an important component of the chicken turtle’s habitat, and they are most common in wetlands where at least 50% of the wetland contains dense vegetation. Most species of emergent or submerged aquatic plants can provide good habitat, but here are a few plant species commonly associated with western chicken turtles:

- American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea)

- Horned Beaksedge (Rhynchospora macrostachya)

- Floating Primrose Willow (Ludwigia peploides)

- Coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum)

- Pondweed (Potamogeton spp.)

- Filamentous Algae (Spirogyra, Anabaena, Oscillatoria, Lyngbya, Pithophora)

- Water Primrose (Ludwigia spp.)

For most of the year, chicken turtles are underground at upland estivation sites. They bury themselves completely, and often dig beneath dense, thorny vines or shrubs for extra protection while they are estivating.

Page 4: Feeding

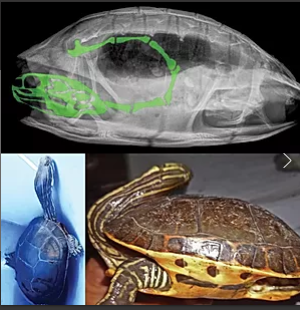

Chicken turtles have a modified hyoid that allows them to engage in suction-feeding, a trait which isn’t common among similar species. Their diet is mostly composed of live crawfish and aquatic insects.

Chicken turtles have impressive necks. They keep them tucked in most of the time for protection, but a chicken turtle’s neck can extend to 70% of the length of the turtle’s shell!

Page 5: Research

The Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute has been conducting research on the Western Chicken Turtle in Texas since 2015. In cooperation with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and Katy Prairie Conservancy, we are learning as much as we can about this species to identify conservation priorities and inform decisions which ensure its long-term survival.

We are tracking turtles with radio transmitters to learn about the movements and home range of this species.

We are performing annual mark and recapture surveys to learn about the growth and survival rates of our chicken turtle populations in Texas.

We are using ultrasound and x-ray technology to study the reproductive biology of female chicken turtles.

Quiz:

- Test your knowledge of the western chicken turtle by taking this quiz: https://arcg.is/1ub85m